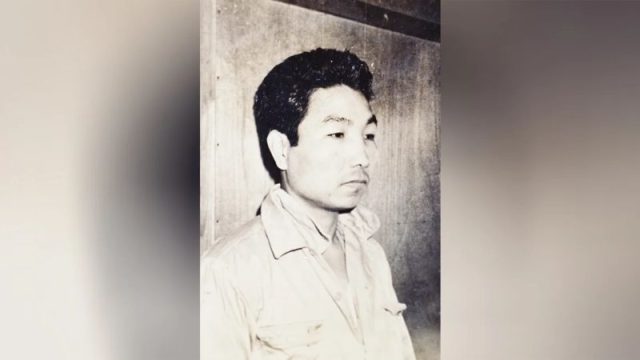

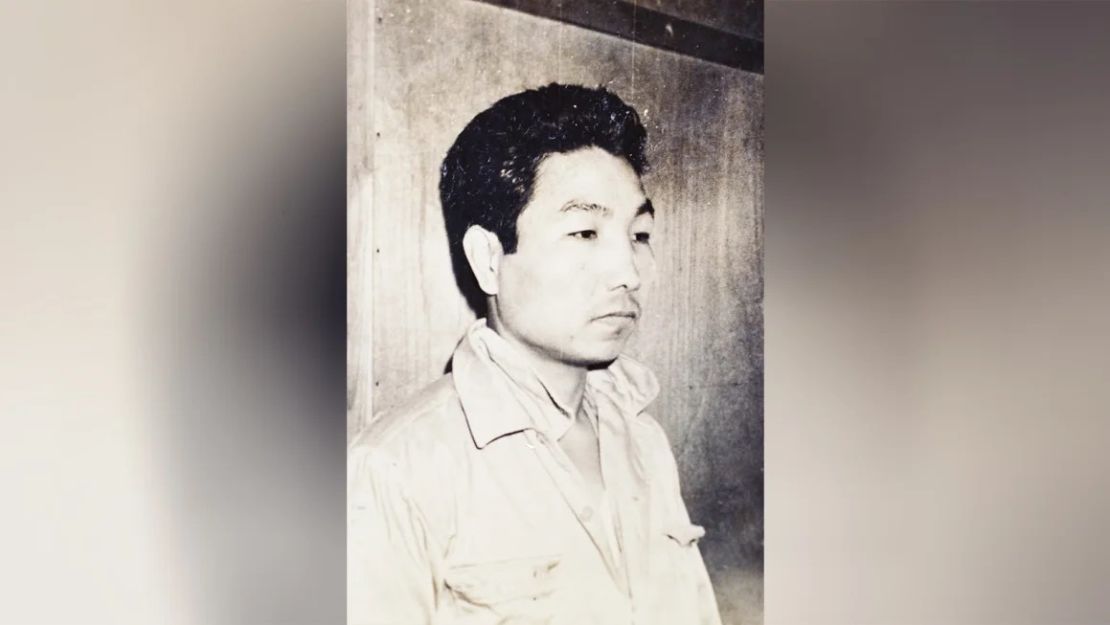

(CNN) – A pair of bloodstained trousers and a forced confession helped send Iwao Hakamata to death row in the 1960s.

Now, more than five decades later, the world’s longest-serving death row inmate has been found innocent, according to public broadcaster NHK.

An 88-year-old man wrongly sentenced to death by a Japanese court for murdering a family in 1968 has sparked global scrutiny of Japan’s criminal justice system and prompted calls to abolish the death penalty in the country.

Judge Kunii Tsuneishi of the Shizuoka District Court ruled that the blood-stained clothing used on the Hakamata convict was planted long after the murders, NHK reported.

“The court cannot accept that the blood stain will be red if it has been soaked in miso for more than a year. The bloodstains were processed and hidden in the tank by the investigating officers after a considerable period of time since the incident,” said Suneshi.

“Mr Hakamata cannot be held guilty.”

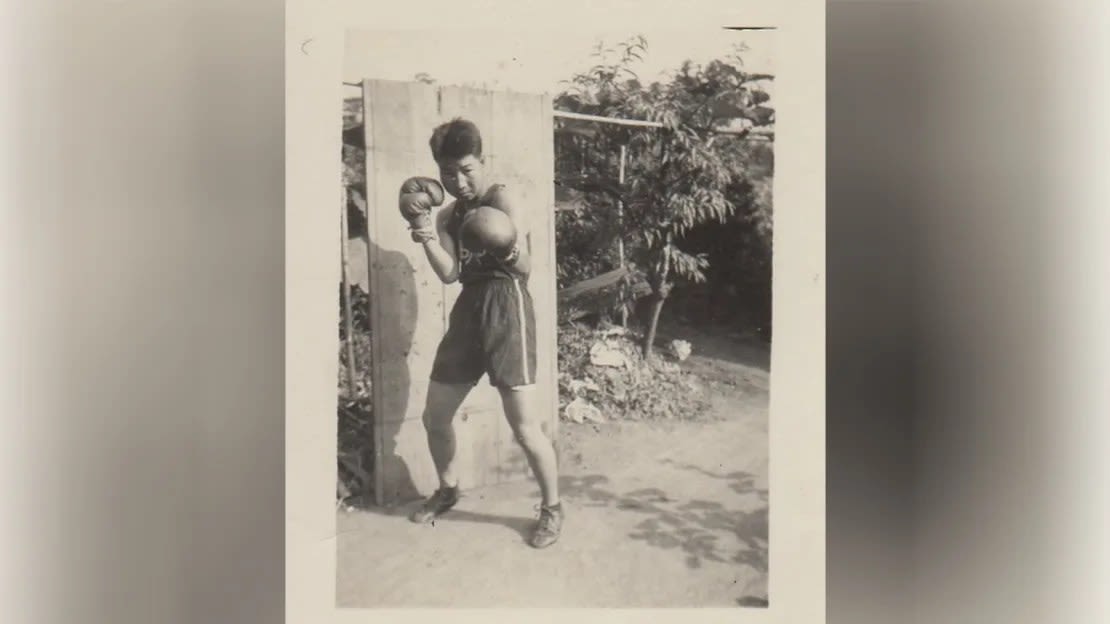

Once a professional boxer, Hakamata retired in 1961 and took a job at a soybean processing plant in Shizuoka, central Japan, which would ruin the rest of his life.

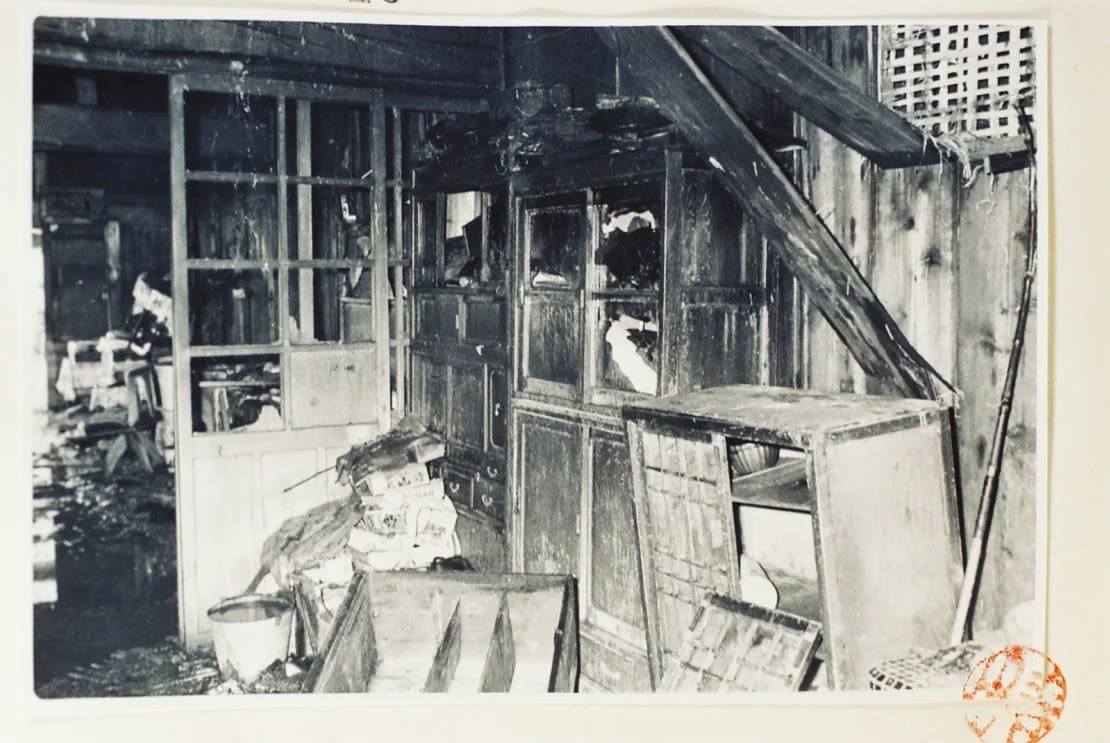

Five years later in June, when Hakamata’s boss, his boss’s wife and their two children were found stabbed to death in their home, Hakamata, then divorced and working in a bar, became the police’s prime suspect.

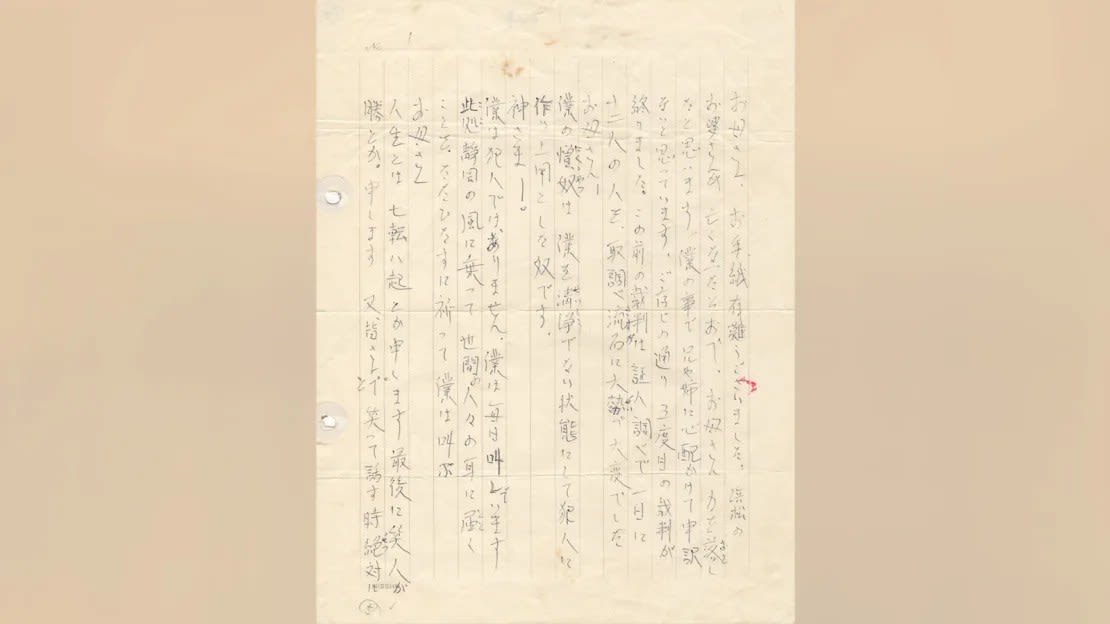

After days of interminable interrogation, Hakamata initially confessed to the charges against him, but later changed his statement, arguing that the police forced him to confess under beatings and threats.

Jurors sentenced him to death by a 2-1 vote, despite repeated claims that the police had fabricated evidence. The lone dissenting judge resigned after six months, frustrated by his inability to stay the verdict.

Hakamata, who has maintained his innocence ever since, would spend more than half of his life awaiting execution before new evidence led to his acquittal a decade ago.

The Shizuoka District Court ordered a new trial in 2014 after DNA tests on blood found on the pants did not match Hakamata or the victims. Due to his advanced age and feeble mind, Hakamata was released while he awaited his day. In court.

The Tokyo High Court initially rejected the request for a new trial for unknown reasons, but agreed to give Hakamata a second chance in 2023 at the behest of Japan’s Supreme Court.

Retrials are rare in Japan, where 99% of cases end in conviction, according to the Justice Ministry website.

Hakamata’s 91-year-old sister, Hideko, said she “couldn’t stop crying, the tears flowed” when she heard the verdict.

“When the judge said the accused was innocent, it seemed divine to me,” said Hideko, who has spent more than half his life campaigning for Hakamata’s innocence.

Hideo Ogawa, Hakamata’s lawyer, called the verdict “groundbreaking” and said “58 years is too long”.

Although his supporters applauded Hakamata’s release, the good news may not have reached the man.

After decades in prison, Hakamata’s mental health has deteriorated and he “lives in his own world,” said Hideko, who has long campaigned for his innocence.

Hakamata rarely speaks and doesn’t care about others, Hideko told CNN.

“Sometimes he smiles happily, but that’s when he’s unconscious,” Hideko said. “We did not discuss the investigation with Iwao due to our inability to identify the truth.”

But the Hakamata case always revolves around more than one man.

This has raised questions about Japan’s reliance on confessions to secure convictions. Some say this is a reason to abolish the death penalty in the country.

“I am against the death penalty,” Hideko said. “Prisoners are human too.”

Japan is the only G7 country outside the United States to retain the death penalty, despite not carrying out the death penalty in 2023, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

Hiroshi Ichikawa, a former prosecutor not involved in the Hakamata case, said Japanese prosecutors were historically encouraged to obtain confessions before searching for evidence, even if it meant threatening or manipulating defendants into confessing their guilt.

The emphasis on confessions is what allows Japan to maintain such a high conviction rate, Ichikawa said, in a country where acquittal can severely damage a lawyer’s career.

For 46 years, Hakamata has been in prison after being convicted on the basis of stained clothing and confessions he made at the insistence of his lawyers.

Hakamata’s lawyer, Ogawa, told CNN that his client was physically restrained and interrogated for more than 12 hours a day for 23 days, without a defense lawyer present.

“The Japanese judicial system, especially at that time, was a system that allowed intelligence agencies to use its secretive nature to commit illegal or investigative crimes,” Ogawa said.

Chiara Sangiorgio, Amnesty International’s death penalty adviser, said Hakamata’s case was “symbolic of many problems with the criminal justice (system) in Japan”.

Death row inmates in Japan are typically held in solitary confinement with limited contact with the outside world, Sangeorgio said.

Executions are “shrouded in secrecy” with little or no warning, and families and lawyers are usually not notified until after the execution.

Hakamata has spent most of his life in prison for a crime he did not commit.

However, despite his poor mental health, over the past decade Hakamata has been able to enjoy some of the small pleasures that come with living independently.

She adopted two cats in February. “Iwao started focusing on the cats, taking care of them and taking care of them, which was a big change,” Hideko said.

After delivering the verdict, the judge, clearly emotional, apologized to Hideko, NHK reported.

“The court is very sorry that it has taken so long.”

Hideko wiped her tears with a handkerchief.

CNN’s Nodoka Katsura contributed to this report.