(CNN) – Exploration of one of the most promising environments for life in the Solar System is about to begin.

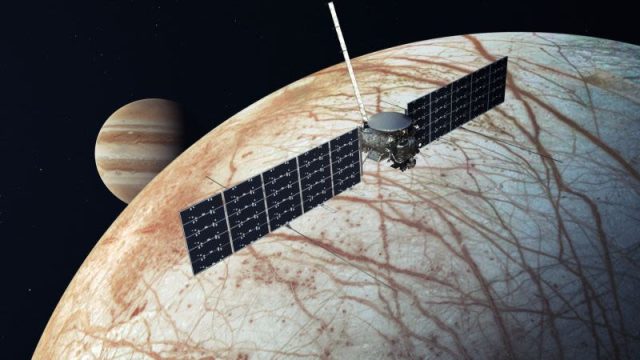

NASA’s Europa Clipper space probe, designed to explore its namesake moon Europa, will launch Monday at 12:06 p.m. ET on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The event will be streamed live on NASA’s website beginning at 11:00 a.m.

According to Mike McAleenan, a meteorologist for the U.S. Air Force’s 45th Weather Wing, weather conditions are 95% favorable for a liftoff.

If the Europa Clipper does not depart this Monday, there are launch opportunities until November 6. According to Tim Dunn, senior launch manager for NASA’s Launch Services Program, every launch opportunity is immediate.

The long-awaited departure, originally scheduled for October 10, was delayed by Cyclone Milton. However, crews at the center assessed launch pad facilities after the storm and returned the shuttle to the launch pad.

Europa Clipper is NASA’s first spacecraft dedicated to studying icy ocean worlds in our solar system, and is intended to determine whether the moon is habitable for life as we know it.

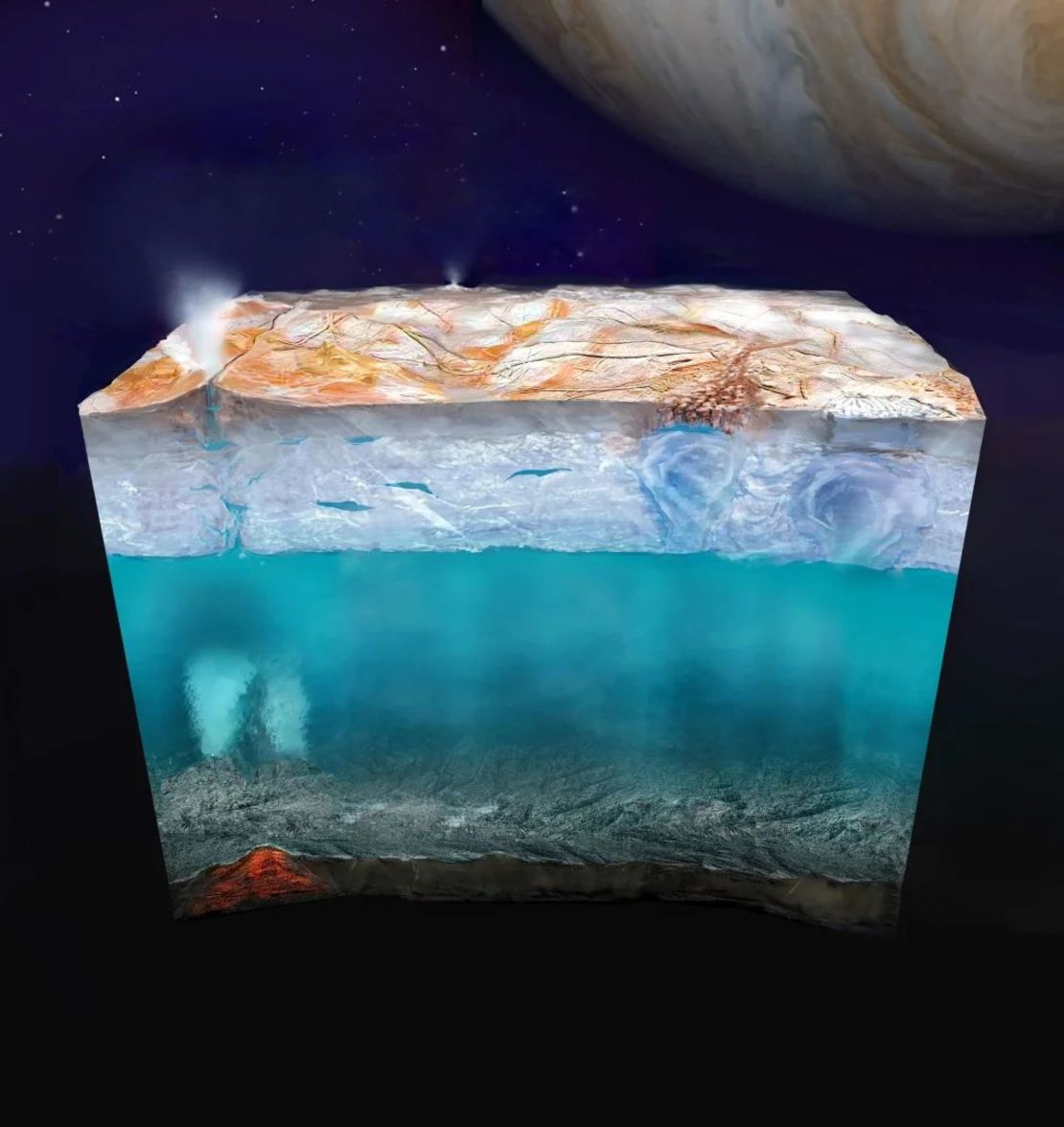

Clipper will carry nine instruments and a gravity probe to explore the ocean beneath Europa’s dense ice. The moon’s oceans are estimated to contain twice as much liquid water as Earth’s oceans.

“The instruments are working together to answer our most important questions about Europa,” said Robert Pappalardo, project scientist on the mission at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. We’ll learn what makes it tick.”

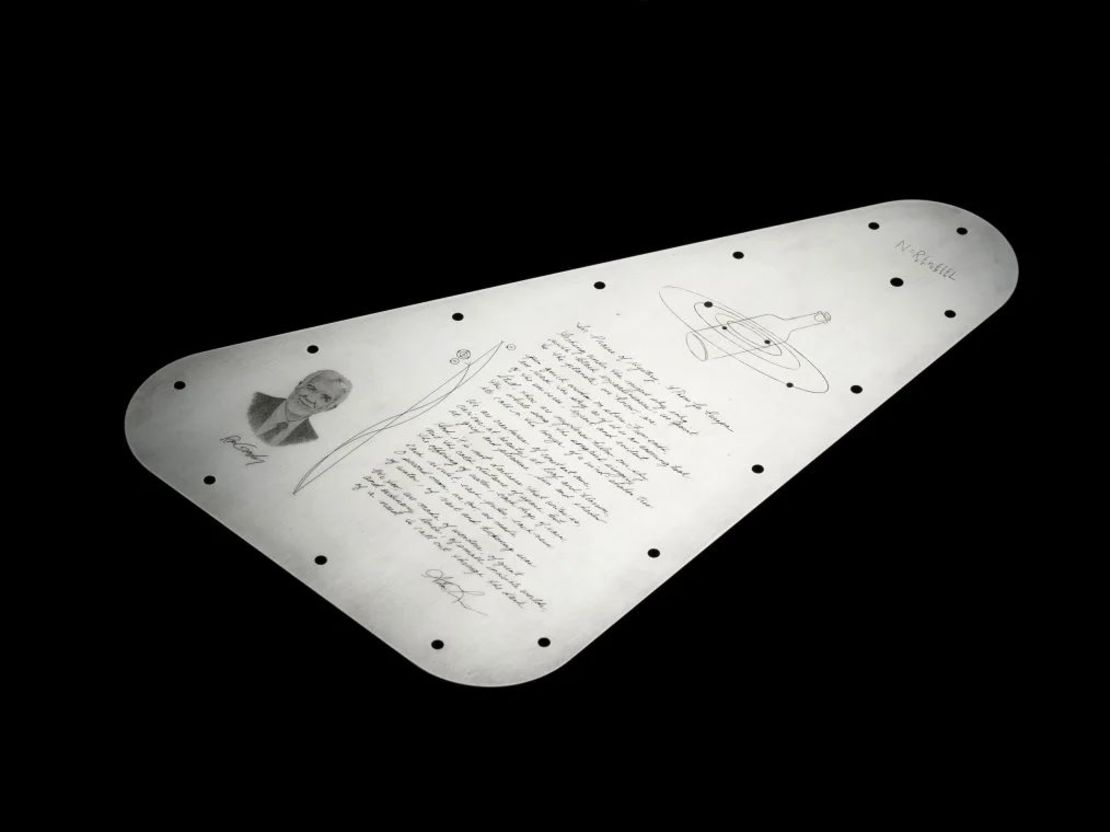

The spaceship features more than 2.6 million names submitted by people from around the world and a poem by American Poet Laureate Ada Limon.

The $5.2 billion project began as a concept in 2013, but the road to launch was not without challenges.

In May, engineers discovered that the spacecraft’s components could not withstand Jupiter’s harsh radiation environment. However, the team was able to complete the required testing on time and receive approval for launch in September, avoiding a 13-month launch delay without any changes to the mission plan, objectives or trajectory.

“There has never been a more difficult year to get Europa Clipper to the finish line,” said Kurt Nieber, Europa Clipper project scientist.

“But all in all, one thing we never doubted was that it would be worth it,” Niebuhr said. “This is an opportunity to explore not the world that was habitable billions of years ago, but the world that is habitable today; The first study of this new type of world we recently discovered, which we call an ocean world, is completely submerged, submerged in liquid water, and looks completely different from what we’ve seen before. That is what awaits us in Europe.

After launch, the spacecraft will travel 1.8 billion miles (2.9 billion kilometers) and is expected to reach Jupiter in April 2030. Along the way, the spacecraft will fly by Mars and then Earth, using each planet’s gravity to help the spacecraft navigate. Low fuel and gaining speed for a trip to Jupiter.

Europa will work alongside the Clipper JUICE or Jupiter IC Moons Explorer spacecraft, launched by the European Space Agency in April 2023, which will arrive in July 2031 to study Jupiter and its largest moons.

Clipper, the largest spacecraft NASA has ever built for a planetary mission, is 30.5 meters wide (wider than a basketball court), thanks to its solar panels. The massive panels will help absorb enough sunlight to power the spacecraft’s instruments and electronics during its exploration of Europa, which is five times closer to the Sun than Earth.

Once there, the spacecraft will conduct 49 flybys of Europa instead of landing on the moon’s surface.

At first, mission teams feared that Clipper would not be able to withstand Jupiter’s harsh environment because the giant planet’s magnetic field (which traps and accelerates charged particles and produces radiation that can damage the spacecraft) is 20,000 times stronger than Earth’s. But engineers found a way around this problem.

Each flyby of Europa, scheduled every two to three weeks, will see the spacecraft spend less than a day exposed to Jupiter’s intense radiation before taking off again. The time between steps helps the spacecraft’s transistors, which control the vehicle’s electrical flow, recover from radiation exposure.

Meanwhile, a specially designed dome made of titanium and aluminum will protect the spacecraft’s sensitive electronics from radiation.

Finally, flybys will carry the Clipper up to 25 kilometers above the surface, each time flying over a different location in Europe. This strategy would allow the spacecraft to map the entire moon.

Once the mission is complete, the spacecraft’s journey will end with a collision with the surface of Ganymede, Jupiter’s largest moon, although that has yet to be determined.

Europa Clipper is not designed to look for evidence of life on Europa, but will use a series of instruments to see if life is possible within an ocean in our solar system.

Astronomers believe that the ingredients for life, such as water, energy and the right chemistry, may already exist on Europa. Probes can gather evidence to determine whether those materials combine to make the Moon’s environment habitable.

The mission will determine the exact thickness of the ice that surrounds the moon and how that icy exterior interacts with the ocean beneath it, as well as characterize the moon’s geography. Scientists are interested in knowing the exact composition of the ocean and what causes previously observed plumes from cracks in the ice and ejecting particles into space. They also want to determine if material from Europa’s surface is seeping into the ocean.

To carry out detailed research, the Europa Clipper is equipped with cameras and spectrometers to capture high-resolution images and create maps of the Moon’s surface and its thin atmosphere. The spacecraft also has a thermal instrument to detect ice plume activity and places where the ice is warm. A magnetometer would probe the moon’s magnetic field and confirm the presence of Europa’s ocean, its depth and salt content.

An ice-penetrating radar lies beneath the outer layer, estimated to be 15 to 25 kilometers thick, to look for evidence of a lunar ocean.